Are you a worrier?

- Are you constantly considering:

- what might happen or

- what you wish you would have done differently?

Do you have a hard time turning it off?

Or, are you afraid to stop worrying for fear that you will miss something important?

If so, this post is for you – well it is really for anyone with a pre-frontal cortex and that would be all of us!

Why a prefrontal cortex? The prefrontal cortex is the most  recently developed part of our brain and, as humans, it is much larger and more highly developed than most other mammals.

recently developed part of our brain and, as humans, it is much larger and more highly developed than most other mammals.

The prefrontal cortex is the part of the brain that allows us to think and reason. It allows us to see all of the various aspects of a situation and to reflect on the past, as well as plan for the future.

Do you see how having a more highly developed prefrontal cortex would make us susceptible to worrying?

Let’s compare what happens when an animal has a close call with death to what happens for us in a similar situation.

Let’s compare what happens when an animal has a close call with death to what happens for us in a similar situation.

Most of us have seen, at least on television, an animal barely escaping death by a predator.

Think back to that wildlife program on television where the zebra or some other poor creature just barely escapes the lion’s jaws. What happens next? Typically the animal shakes off the stress and then goes about its day grazing or resting.

What would happen if a human narrowly escapes death? Would we give ourselves a good body shake and then move on as if nothing had happened? Most likely not.

Most of us would be replaying the situation over and  over in our heads.

over in our heads.

We would be thinking about what a close call that had been and we would almost certainly be thinking about how we could avoid it happening again in the future.

It would be like a dark cloud following us everywhere we go.

All of that thinking and planning is work of the prefrontal cortex. It helps us to be prepared and to learn from our experiences in a way that is not possible for other mammals.

Learning from our experiences and being prepared, based on those experiences, is extremely useful to our survival.

The downside of that is that we can spend much of our time

replaying stressful situations in our minds or

anticipating future dangers

all while we are safe and sound sitting on our couches with our families enjoying what could be a relaxing evening.

Unfortunately, besides ruining a relaxing evening, every time we replay that horrifying experience or imagine a horrifying event about to happen, our body responds as if the event is actually happening.

Stress hormones rise and the brain records the event to help us be more prepared to face it in the future – when in many cases it has never happened in the first place!!

Our brain/body doesn’t differentiate between what is actually happening and what we are vividly imagining.

Our brain/body doesn’t differentiate between what is actually happening and what we are vividly imagining.

This is why imagery is so effective. If you are imagining sitting by the ocean on the beach and feeling relaxed, your body will experience this relaxation.

If you are imagining some horrible thing happening to you, your body will respond as if what you are imagining is happening right now. It doesn’t matter that you are actually safe and sound at home.

So here is the tricky part. It is helpful to be prepared. That is one of the advantages of having such a highly advanced frontal cortex.

However there is a difference between planning and worrying. Ineffective worrying increases our stress levels and fears about the future. It can also lead to anxiety.

This is where learning how to worry, effectively, comes into play.

I would like to share with you a tool that many of my clients have found helpful in learning to be more effective with their worrying.

To understand why this tool is effective it is helpful to think of a scared child. Parents are much further ahead if they acknowledge a child’s fear than if they simply try to ignore the child or tell the child they will be fine without really listening to why the child is afraid.

To understand why this tool is effective it is helpful to think of a scared child. Parents are much further ahead if they acknowledge a child’s fear than if they simply try to ignore the child or tell the child they will be fine without really listening to why the child is afraid.

If a child is afraid there is a monster in the closet, responding with “no there isn’t, go back to bed” probably isn’t going to be very effective, right?

It is pretty similar with our emotional brain.

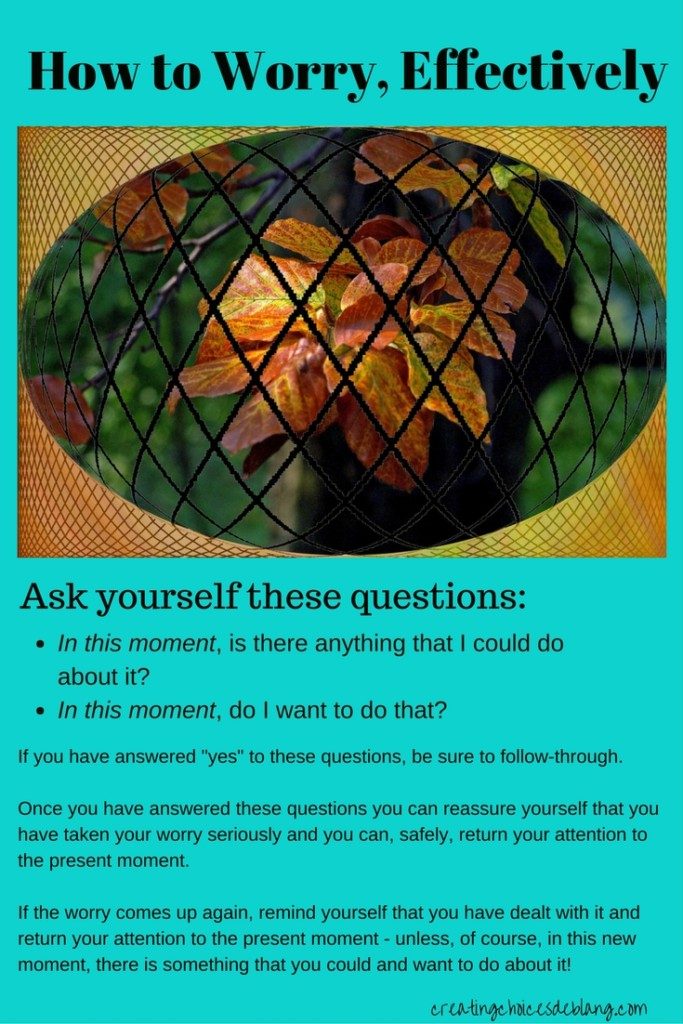

The tool consists of two questions, with the most important part of each question being “in this moment”.

Here is the tool:

Click here if you would like to download a copy.

So, let me give you an example. This is the example that I most often use with clients. Most of the time it generates a chuckle because people get the absurdity of my continuing to either ruminate on it or take action on it while I am with them in session.

In the example, I share with my clients that my car was making a funny noise as I drove to the office that morning. I let them know that I keep worrying about whether it will start when I leave to go for lunch. I share my worries that I will be stuck, etc.

I then give them an example of using the tool.

I ask myself the first question. “Is there anything that I could do about it in this moment?”

“Is there anything that I could do about it in this moment?”

Well yes, I could say to my client, “excuse me, but I need to run out to my car and make sure it will start.” Or I could say, “Excuse me, but I want to call someone to be sure they will be available in case my car won’t start at lunch.”

Most times, clients are already chuckling at the absurdity of this.

Then I ask myself the second question. “In this moment, do I want to do that?”

And, of course, the answer is no. I would not want to interrupt my session to run out to the car or to call a friend!

I have now effectively addressed the worry. I have done all that I could and would want to do about it. That does not mean that the worry will always just go away. Sometimes it will and other times it will continue to circulate.

So, think again about a child who is worried, one reassurance may not be enough. A parent may need to both reassure and redirect, saying something like, “remember we already took care of that – let’s do this right now” – whatever the “this” might be.

That is where those mindfulness skills come in. If you are unfamiliar with mindfulness, check out my previous post.

Once you have done all you can and want to do about a worry and that worry is simply recycling the next step is to remind yourself that you have already dealt with that concern and that you can safely return your attention to whatever it is that you are doing in that moment.

This is important because what we attend to is what we experience and so once you have answered the questions it is important to bring your attention back to the present moment and the task at hand. Continuing to focus on a worry that has already been dealt with will only increase your anxiety.

Take a moment to, once again, to think about a child who is afraid. Once a parent has helped the child to feel secure that they have done all that can be done the parent is certainly not going to encourage the child to sit and worry about it. Make sense?

The worries still may circulate and the task is to deal with them and then use our mindfulness and attention skills to allow them to be in the background without triggering a stress response.

Let me give you another example of using this tool.

One of the reasons this tool is so effective is that it allows you to feel reassured that you will keep yourself safe – if there is immediate danger you will notice and act and if there is an impending danger, you will be prepared.

Let’s imagine that I am heading out into the woods in bear country.

If I notice that I am worrying about bears in the woods, saying something like “Oh, I’m not there yet, I will just deal with them if I see them” probably doesn’t make much sense, right?

It is unlikely to quiet my worries or keep me safe.

If I notice myself worrying, asking myself the two questions would be much more helpful.

Is there something I could do? Well yes, I could get some bear spray and learn how to use and carry it. Do I want to do that – of course.

Once I have done that I am as prepared as I can be at this moment, right? Well, I could use my imagination to practice effectively using the bear spray and surviving.

When I have done all that I can and want to do, I need to use my mindfulness skills to notice when the worry has resurfaced, reassure myself and redirect my attention.

If, instead, I spend hours worrying about bears that I might encounter and whether I will be safe, what is likely to happen?

I will probably be too anxious to go and if I do go, I will most likely either be paralyzed or extremely anxious. Neither of which is a very effective place to be if in fact I do encounter a bear.

Worries can help you be safe and prepared or they can easily lead to anxiety which can be paralyzing.

This tool has the potential to help you deal more effectively with worries so that they don’t spin into anxiety. It can also help you to feel secure that will keep yourself safe.

When it comes to tools, finding the ones that are  the most helpful for you is important. I would suggest you give these questions a try and see if this might be a tool that you add to your toolbox for help with worrying.

the most helpful for you is important. I would suggest you give these questions a try and see if this might be a tool that you add to your toolbox for help with worrying.

I hope that you have found this post helpful.

Sometimes we are just too far in the stress response to be very effective with our worrying. Stay tuned as I plan to write about suggestions for dealing with what I call the “desperate” state.

If you would like to receive notifications when new posts are published, simply sign up to the right and up top.

0 Comments